I'm not going to lie: the future scares me. The only thing more certain than my fear is the knowledge that I'm not alone in it.

Every day after a certain point in my life (a point that's proving exceptionally difficult to pinpoint), I began taking future quandary seriously. And what I saw...I didn't like.

It wasn't that I didn't have a future. I was always certain I did.

It wasn't that it was going to be difficult that I didn't like. I enjoy challenges, regardless of whether they're even relevant or necessary, or even worth pursuing in the least. A challenge is a challenge, and I'd climb a mountain just because it's there (except I wouldn't actually. I'm terrible with climbing).

No, what I didn't like was its murkiness. I always thought about it this way: to me, no way of dying is more terrifying than death by shark attack. I could be mauled by a tiger, fall out of a plane or cliff, or get hit by a truck, but just the thought of being consumed by a shark...well, it gets me in a way I'm not often got.

Why? Because up until they set their jaws in your skin, you don't see them clearly. You only see a silhouette distorted by the waves, unless you're looking at them through goggles. But regardless, it's that uncertainty of form that carried with it terror, dread, and a death less than ideal.

And so it is with the future. It's murky, and always will be. It was back then when I first began wondering about it, and it is now, even at the start of my graduate studies (although not so much the start anymore).

Will it ever be different? Will I ever have the certainty and comfort in knowing the future? Conceivably not.

I always hated leaving things in the hands of fate. But, ultimately, such things may just be out of our hands, no matter how much we struggle to control our world. Although I'm still on the fence on whether I'd prefer fate or absolute chaos (I have my theories that you either have one or the other, but that's a discussion for another day), maybe my notion of control is just an illusion...

Fine, I can live with that. But dammit if I'm going to surrender my autonomy without first dying for it.

Now, I am a cognitive scientist, which places me in a larger set of people: that consisting of scientists. Science is itself a mushy label with an equally mushy set of meanings. We have enough pseudo-sciences in existence to rival the whole accomplishments of what we would consider "real" science, as well as an equal number of people who would gladly hold their pseudo-science up against the most complicated tenets of string theory and quantum physics. Point is, what makes a field science is rather poorly defined, and I honestly don't see any rigorous or formulaic means of simplifying and defining the distinction itself.

What we can all agree on, at least to some extent, is that science is concerned with questions. These questions are big and small, perplexing or perhaps simple, of interest to us or not. Questions of matter, of existence and metaphysics, the nature of life, thought, our bodies and our minds. Questions of how we came to be, how things came to be the way they are, and how things could conceivably change or become. Science is composed of questions of all kinds.

Humanity, and even more so its scientists, find themselves in the middle ground of the universe and its questions. On a grand scale, we are caught between the beginning of time and the end of time. We are always wandering between ignorance and complete enlightenment, looking back at what we've learned through eons of experience and study as well as staring forward into all of the things we have yet to understand to even the slightest iota of truth. On a more individual scale, we display the same patterns of middle ground-ing. We neither always love, nor always hate. We are intelligent in some places, idiotic in others. We think we're better than some people, others we wish we could be instead. We're brave...sometimes. We're also cowards too of course. We're a middling and meddling species no doubt.

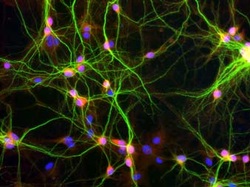

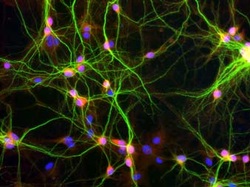

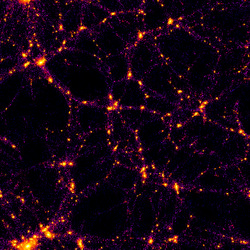

So it was a sort of "philosophical justice" when I realized that, in my mind, we are once again caught in the middle ground of two of the major questions facing science and humanity in the 21st century: the workings of the mind and the depths of the universe. The study of the human mind can be considered very roughly along two levels of analysis: high-level function and behavior, and biological/physiological changes that occur on the neuronal level. Regardless of which level of analysis you choose to focus on, the closeness of the object of understanding is as close to us as anything is. It forms the central core of any human and animal, and any conception of existence would be (quite literally) impossible without it. We can poke it, dissect it, (try to) replicate it in computers, hold it in our hands and take notes about its squishiness, and observe the end results of its functionality in ourselves and others. The mind is as close to us as anything could ever be.

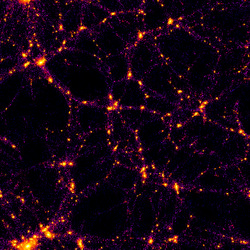

Stretching beyond our ability to touch, feel, or grasp is the sheer immensity of the universe. We have barely scratched the edges of our own atmosphere and remark to ourselves about how great an accomplishment that is (and don't get me wrong, it is a great accomplishment), and yet we all realize that we have only descended one inch into the depths of a great ocean of stars. Out there is something we can't grasp, something we can't hold or manipulate with our fingers. We can't poke it, we can't dissect it. We are instead largely confined to staring at it and marvelling at its splendor and awesomeness. It is as far from our grasp as anything could ever be.

Through this stark constrast, they share an important attribute: they embody two of the great mysteries that challenge the human race. As I mentioned before, science is about questions, and they don't get much bigger than this. To put it succinctly, the big questions for us are "what is the nature of that which is outside of us and beyond our grasp?" and "what is the nature of that which occurs inside of us, within the confines of our own bodily limits?"

So we are in the middle of two great mysteries, searching in both directions for answers to that which is closest to us and that which is farthest from us. In a telling moment from the Tron movie series, we are treated to two opposing rallying cries:

"In there...is our destiny."

"Out there...is our destiny."

For humans and scientists, whatever our destiny may be, it does not appear to have drawn any such distinctions between what is in there and what is out there. It is simply destiny.

There are a lot of mushy ways to define meaning. As a lexical semanticist, I can think in starkly academic terms the meaning of...meaning. But as a human being, there is a lot more weight to the word than can be lexicalized. At least formally.

So let's consider for a moment what I mean when I say "meaning." When I apply the term to the overall human experience, it pertains to something that gives a moment, a period, or a lifetime something of importance. Thus, meaning to me is considered at least in part to be temporally relevant. It is as temporally relevant as the fact that when we walk, there must be one step that occurs after each step, and ongoing until we decide to stop. It doesn't matter how far we can break down our experience over a lifetime, the meaningful things are always there.

Finding meaning is perhaps even more difficult than defining it. Perhaps it's one of those "I don't know what it is, but I know it when I see it" kinda deals. The good thing about this approach is that it relativizes what is meaningful to a person to the person itself. Thus, there are many approaches to life, and meaning comes to everyone in unique ways, as it is uniquely defined by that individual.

Regardless, I still feel as though meaningless acts and lives are not uncommon. Perhaps it is difficult, even impossible, to judge fairly the way people search for meaning in their lives. Regardless, if one didn't have some notion of what they felt was a waste of life then they wouldn't be able to guide any of their important decisions, much less themselves live a meaningful life under their own definitions.

So I judge...it's impossible not to. And it does sadden me a bit to see people sometimes surrender the desire for a meaningful life, and waste time with meaningless actions.

But these judgments are all through the eyes of ones own definitions, and are implicitly unfair as a result. What's important is realizing this, and understanding there are many different ways people find meaning.

I'm certain someone out there after all finds the way I've chosen to live my life is meaningless and wasteful (anyone who's ever criticized me for selecting Philosophy as a course of study would agree). Ultimately, you can only shake your head, and hope they themselves realize to see things through your eyes.

It'll never happen of course, but it's a nice thought.

The statistical revolution changed the face of modern AI, and resulted in a desertion from rule based systems, in favor of the promise that pure statistical processing had. Vast data corpuses are en vogue, processed with counting, totalling, probabilizing, and any other kind of statistical mechanism that yielded incredible performances for particular tasks.

It seems as though there is no limit to what you can do with statistical processing. Natural language, rather than being viewed as an inherently psychological and linguistic domain that struck at the heart of what it means to be conscious at a human-level, has become a stomping ground for blind numbers to run about unchecked. Powerful, simple, and very reliable, it's where the funding is.But, without being long-winded, I'm going to tell you that statistical processing will never realize by itself the grand hopes we once had.

Those researchers in AI once had these dreams of truly trying to understand the human psyche, what it means to be conscious, and a host of other philosophical quandaries that for eons have been the sole domain of armchair thinkers and dreamers. Somewhere along the way, many compromised and followed the money, the promise, and the success of blind numbers.

These numbers are just that though: blind. The first generation of AI researchers failed because they believed that they could continuously throw rules and facts at real world problems, and eventually their store of explicit cases would be so great it would match the human computational capacity and consciousness or something like it would result.Time has shown this to be impossible, and fundamentally flawed.

Why? Because you can't brute force your way to an understanding of human nature!

Humans are intricate, delicate, and defiant of what rules we could ever make explicit it seems. Especially when those rules are...blind.Purely statistical methods will hit a performance ceiling that is the result of the same fundamental philosophical flaw: pure numbers are blind. They do not understand the concept of what it means for something to have edges, to have color, to have a taste or touch or feel. Numbers can encode things, but they can't embody them. Statistical methods can analyze data, but they can never truly generate data themselves. Statistical methods can only pretend to be generative of concepts, but can never truly be generative on a level that we could consider human.

This is not to say that rule based methods are the answer (and in fact, I do not believe that human cognition will ever be solved, be it by rule-based or statistical methods), but to hold statistics as the key is just misleading oneself in to the delusion that success is just around the corner.

Numbers are blind! You can't brute force your way to understanding nature!

The ceiling someday will be hit. Ultimately, you will need rule based systems, with statistics, in order to continue making progress.

That's my prediction.

Understanding the human mind better is not a simple game of blind numbers and blind rules.

It's the game understanding ourselves.

Words are a fascinating little thing, the constituents of communication. We use them for everything, from ordering a hamburger to ordering our two-year old off the coffee table. They can be poetic, or they can rough. They can be fluid, or they can be broken. They can make sense in particular arrangements, be totally impossible to understand in others, and covering every space in between those two ends.

I'm thinking these days about emotionally loaded words. Consider some classics:

adore

kiss

hold

touch

l#ve (censored for the faint of heart. it is a four letter word after all)

This five words are a tiny fraction of words that could have significant emotional meaning. Of course, emotional meaning is contingent upon pragmatic factors. For instance, to say "I adore donuts" has less emotional weight than expressing the same verb to take as its object a person of particular value to you (save for donut junkies. You know who you are). However, when placed in the emotional environment as I just did, many of us can already picture moments from their past where these words went beyond simply a lexical definition that fit into a grammatical framework.

These little pieces, little building blocks, when in the right place both grammatically and pragmatically, have invisible strings that tie themselves to parts of us we have little conscious access to. We do not even need to put them in particular concrete contexts to feel something about these words, something intuitively special about their usage and their weight.

We can say things are only words, but we all should know better. Yes, in some sense they are only words. My very first car was, well, only a car (and honestly, not a very good one at that). However, just its place in my memory makes that car more than just a car to me. It's something personal to me, more important than just another car I may see driving down the street.

I'm sure we all can relate in some way, and so it is with words. We all have very different experiences tied to words of emotional relevance, yet I hypothesize that they all generate similar feelings within each of us. On some level, we can all relate with each other about words of emotional weight.

So yes, they are only words. But words aren't just a means of communicating ideas. They are also a means of communicating emotions, desires, beliefs, and the things we hold dear and essential to the characteristics that make us who we are. Don't underestimate their weight.

I am currently having another bout with insomnia, my restless mind accelerating through a multitude of thoughts with little to no organization, rhyme, reason, or rhythm.

During this latest uncontrollable mental meandering, my thoughts turned to what it means to be in the field of cognitive science, and of course, A.I. A conversation I had a few months ago with someone caused me to reconsider many of the motivations and aspects of the weight of my work, in ways I'm only now coming to fully comprehend.

Once upon a time, I dreamt of being one of the minds who gave birth to true, strong artificial intelligence. I wanted to create an artificial mind that rivaled that of humans across all domains, to the point where the only thing that separated humans and artificial systems of intelligence would be the origin and biological makeup of the entity.

To me, the effects such a discovery would have on society had never truly struck a chord with me. Despite my philosophical background, I had always considered the work of a scientist to be principally concerned with scientific progress, and the treatment and incorporation into society the work of...well, someone else. After all, we as scientists have enough trouble as it is trying to understand the mechanisms of mind while simultaneously limited to using only our own mechanisms of mind.

Of course, societal impact of true AI had occurred to me. But such things as treatment of these entities, systems of rights, and other such ethical concerns were something I felt perhaps the human race would cope with over time and accrued experience, with ample leeway for growing pains.

In short, societal implications of my work was not my concern.

My thoughts gradually changed when presented with a different view, a new reason for caution.

As it was discussed, it was made explicit to me a realization that anyone who's been in the field of AI for a reasonable amount of time by a person who was not in the field itself: the human mind is a wonderful thing, of great complexity and majesty. There are things that occur within even the most basic of human thought processes that have proven to be extraordinarily resilient to even the most probing of minds and analysis. To try to reduce the majesty of human cognition to a sequence of 1's and 0's is perhaps missing the point of what makes the human mind special.

Think of the human mind as a beautiful one-way mirror. We can "peer" outwards from one side of this mirror, but looking into it from outside, we can only see a reflection of our own eyes staring at its surface, but never through it. The majesty of human cognition is preserved by this one-way mirror, the ultimate treasure we cannot see (yet). Majesty is preserved in mystery.

This was all well and good to me, although the weight of this fact didn't sink in until later. What was especially disturbing to me at the time was the following point made: in trying to create artificial intelligence, we run the risk of shattering the one-way mirror, and destroying what makes the human experience special, magical, majestic.

Our meddling intellect misshapes the beauteous form of things. We murder to dissect.

~William Wordsworth

Will we murder the beauty and mystery of the human mind in order to dissect it? And for what gain? So that we could have another feather to stick in our cap and scream out at the heavens "Look what man's intellect has discovered! Truly, are we not Gods?"

It took many months for me to contemplate this. It's to me a very weighty issue, one that strikes at the heart of my motivations for research. While I didn't want to give up my passion for my research (where our passions lie is largely not up to me anyways), the doubts leaking into my mind wanted of attention, for they spoke to me at a level of truth I could never explicate with words.

My passion for A.I. research and my fear of shattering the mirror both exist within my mind now, and have largely found ways of coexisting within those limited confines. While acceptance of the presence of both is certainly important to maintaining relevant aspects of my life, I have now been considering how they came to coexist together, my desires and my doubts in stark opposition to one another intuitively, yet standing together in my mind side by side. What is the relation to one another that allows me to keep going with my work?

There is at the heart of my research a very strong notion, a very strong opinion: yes, the human experience and the mind are amazing, beautiful, a wonderful harmony of chaos and order mixed in ways we cannot even begin to comprehend. Nor will we ever truly come to comprehend it.

The one-way mirror is unbreakable. We can strike, pound, hammer with all our might, but the very way the mind is constructed is impervious to our attempts at penetration. We are limited to the tools we are given, and these tools leave us poorly equipped to tear down the wall that separates our intellect from our minds.

Simply put, I am of the belief that it is impossible for us to truly understand what goes on in our minds to the level that would allow us to develop a complete theory of mind.

It is important for me to note here that this isn't to say we won't be able to create true A.I. someday. I am simply of the belief that if we are successful in doing so, it won't be as a result of us understanding the mind and its majesty. It will be done by circumventing this impossible problem, if at all.

So where does that leave me, a poor researcher in the field of cognitive science? It leaves me freedom, and the power to pursue my research to the end, without the fear of shattering the one-way mirror and throwing the mystery of the mind to the winds. For I can drive at my linguistics research, my philosophy research, my computer science research, all towards developing a model that would allow a system to understand natural language on some level, perhaps even a human's level, but no matter how deep I get, no matter how sophisticated my models become, they will only be able to stand outside that one-way mirror, and look in on what true majesty is like.

So do not worry (I tell myself constantly), the mystery of what makes human cognition spectacular is safe from our meddling intellects. The beauteous form of it preserved by its very nature, a security by obscurity.

In closing, the most powerful moment of the conversation was an act. It was an act that changed the way I thought, who I was, and who I was to become. It was an act that carries more significance and weight than any infinite sequence of 0's and 1's could ever express.

For just one instant in time, I looked into the one-way mirror, and saw someone standing beside me, smiling back through the reflection.

So I was thinking about the nature of the research I'd like to do over the next few years (however long it takes for me to accomplish what it is I want to accomplish at the graduate student level, be it three or four or five years), and my mind turned to the way language functions between humans (as my thoughts tend to these days). A very simple way for me to break down language was by dividing it into three components:

1. Syntax

2. Semantics

3. Pragmatics

This list is akin to the field of Semiotics, "the study of sign processes (semiosis), or signification and communication, signs and symbols (Wikipedia)."

In short, these three components all combine in a way to enable communication via the use of symbols and signs, and the meaning that these symbols and signs signify. I will need to flesh out these ideas more, but I am curious about what theories of these interactions exist to represent meaning in natural language. Perhaps an implementation of my own theory on Natural Language Semiotics in the cognitive architecture Polyscheme may be in order at some point in the near future...

Well, that's one heck of a mouthful for a title. Let me explain it.

It's been theorized that the foundations for human language use are based on concepts that are intrinsically non-linguistic. That is to say, the basis of language is not on the words uttered, written, or otherwise conveyed in some manner (although this being an integral part of language as we experience and know it), but rather on the words' reference to processes, states, and other abstract concepts concerning extra-linguistic information, where the word attachment to the experience is arbitrary (it could have just as easily developed in the English language that the label "dog" be attached to a motorized vehicle intended for personal transportation, a.k.a. what we call a "car" for instance).

That being said, let us consider the combinatoric nature of natural language syntax and its relation to a canonical form of meaning:

1. "I ate the bagel."

2. "The bagel was eaten by me."

3. "At some point in the past, I consumed a bagel."

4. * "I ate bagel."

... and so on and so forth.

note: "*" means sentence is ill-formed

Examining these sentences, you can see they are all different in one sense, yet identical in another. They are different in that they use different words and in different order. Sentence (4) is not even well-formed as a sentence, yet it is understandable to us native and/or relatively fluid speakers of English what the intended meaning of (4) is.

At the same time, they are identical in the way that pragmatically, they all mean the same thing. Something like:

<tense=past>

<action=eat>

<subject=me>

<directObject=bagel>

That is to say, there is a single canonical form to which all of the above sentences refer to simultaneously. All of the sentences, with all of their lexical and syntactic differences accounted for, still mean essentially the same thing: Before the time of the utterance, I ate a bagel.

Thus, we can see that even with differences in syntactic structure between sentences, they can still mean the same thing. This point I hope is beyond debate, as the previous examples should suffice to convince you of its truth (I hope...).

Here's where the water gets murkier. I will in the next few posts argue shortly for a minimized set of native non-linguistic concepts that can account for the canonical form of sentences that is not wholly defined by syntactic and lexical structure in natural language use. Then I will consider possible forms this set of native non-linguistic concepts that is the base of human natural language understanding through the yielded canonical form representation. Once we have postulated a method of representing the canonical form of natural language, I will then consider the form of a possible interface that exists between the syntactic and lexical composition of a natural language utterance or set of utterances (for instance in dialogue and discourse).

What this hopefully should yield is the beginning of a research goal for the future, where I can continue to explore the nature of the syntax-semantics interface with an eye towards:

1. Natural language origins

2. Natural language use

3. Cognitive underpinnings of natural language understanding

Kind of a big question, huh.

Keep in touch.

I will be shortly commencing my work for the Human Level Intelligence Laboratory at RPI. I feel it necessary to clarify for myself and others the intention of my research and my ultimate goals in terms of what I wany my work to mean.

While it is intriguing on some level to consider the possibility of developing artificial intelligence on the level of humans and begin creating humanoid robots indistinguishable across many features from humans, it is a classic endeavor fraught with pitfalls of pride, arrogance, and danger. What the problem boils down to is an attempt to be god, to match god on some level, to create the majesty of life with our own hands. And not just any form of life. Although it smacks of arrogance, to create human-level intelligence would be to create the ultimate being we can even conceive of. Humans are a wonderful species, and replicating it in all of its dynamism, power, flexibility, capability, and ability would be one of the most significant accomplishments of science and mankind ever. All of the hyperbole aside, this achievement would vindicate minds and ideas, open new doors to new futures, create a whole new set of concerns for the next generations, and bridge the gap between reality and the strangest and most unique ideas within our imaginations. The world would change in ways we cannot even comprehend.

However, it is dangerous. We could become gods, create the beings that would replace us. It doesn't need to occur in some doomsday scenario ala "Terminator." It could be much more subtle, it could be much more dramatic. It could be both in different ways in different spheres of the human experience.

If we come to truly, deeply understand the majesty of the human mind and create it from the ground up, with these hands that just a few millenia ago were dedicated to working with rocks and sticks as opposed to digital computers, are we invading the region of reality that we have no business being there beyond the capacity of a visitor? Even with all of the gifts that true, strong AI could give us, is this something we deserve?

I work for the Human-Level Intelligence Lab, but I have no desire to create artificial humans, beyond imagining it in my mind as a thought experiment. I am a cognitive scientist, and I'd like to take ideas of how humans process information and make decisions and from those ideas and modern computing create technologies that assist humans. I want to help people with technology, not create a replacement for them.

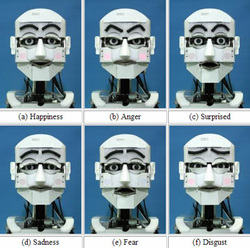

There are some things that belong to humans, regardless of whether we have the capability to create them or not. Things that should not be granted from our hands to our creations. Things like sadness. Things like happiness. Things like anger. Things that technology can't mimic, shouldn't mimic.

Where does my motivation to speak on this topic come from? We as people are capable of great things, and as a whole have shown a propensity for remarkable progress on so many fronts. We have potential for all of the things we could possibly conceive of.

However, all of that aside, the human race would not be prepared for the weight of such responsibility. To hold the fate of a new race of sentience in our own hands? These same hands that have enough trouble determining the value of the life of one of their own? How could we ever responsibly treat a new form of sentience when we've shown such a propensity for destroying members of our own species?

From a more personal level, I've also come to realize the very majesty of the human experience comes from the things technology hasn't yet come to understand, and hopefully never can. However, if/when scientists finally can attach a number to the human experience in whole, I hope that humanity will have progressed to the point where we could handle the world that will spring forth from our hands.

But for now, from a cognitive scientists standpoint, the amazing thing about this work is that it's complexity teaches you to appreciate just how incredible we humans are, and the experiences we are capable of having and using.

What makes my work so difficult is also what makes my life so wonderfully intricate.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed