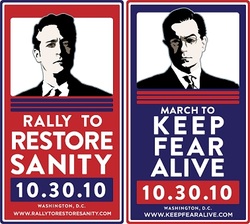

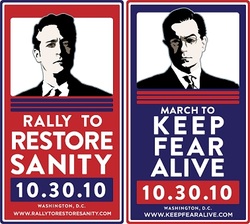

I was originally intending this weekend to attend the rally being staged in D.C. this weekend, hosted by Comedy Central personalities Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert.

Unfortunately, I was unable to head down to D.C. due to a list of items I need to do here (graduate school isn't all fun and games). So, instead, I am working out of one eye, and watching the live web stream of the rally out of my other. Multi-tasking? Like a boss.

That being said, the intention of the rally is, as you could infer from the titles (and taking into account the tongue-in-cheek character of Stephen Colbert), is to call us back to reason. It seems we exist in tempestuous times with an ever more polarizing political climate. Midterm elections are coming up, and for Democrats it appears as though the shift in power to their side may be rapidly coming to a close, if not now in the near future.

The many people who first helped place many Democratic leaders into power in the first place are disillusioned, the magic that permeated the 2008 campaign wearing off to reveal a pumpkin.

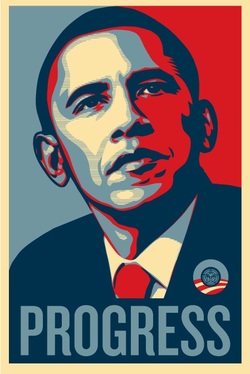

I hate to say I told you so, so I won't. But for us who do prefer sanity, as the rally mentioned above hopes to bring back to the forefront, it was easy to predict this. Let's start at the top: President Barack Obama.

Many of us who supported Mr. Obama during the 2008 presidential campaign made him to be some kind of god. We portrayed him as Superman, one capable of things never before accomplished. We thought him a legend before he had actually accomplished anything at the presidential level, and we annointed him based on potential rather than accomplishment.

It was, to me, insane.

I supported him, and I thought him the best candidate for the job. But the people on his side were simply, for lack of a better word, insane. I just wanted to take so many people by the lapels and shake them, and tell them "No! He's only a man!" Albeit a good one, and well qualified for the position of president.

Unfortunately, it's insanity that helped put him there, rather than real, honest assessment of who he is and what he can do. Please, put away the capes people. You elected a man, not a god.

In these times, we could all use a little bit more sanity, and that applies to all people in all parties. For those people who still think Obama's a god (and I suspect there are fewer of you now than 2008): be reasonable! For those who flip flop from one extreme to the other: be reasonable!

People aren't gods. Neither are they demons. I assure you, Obama can't save the world with his power. At the same time, I assure you, John McCain would not have destroyed the world had he been elected. George W. Bush was not the spawn of satan. Dick Cheney is not an American mini-Hitler. Rush Limbaugh in my opinion is still a douche, but he's entitled to his opinions.

Regardless, let's be reasonable for once. And have reasonable expections as well.

When one looks in the mirror, a typical concern is the appearance of aging. Little wrinkles that appear at the corners of our eyes and mouths, paths formed along your face by the constant treading of facial expression. A little reminder of the unavoidable: you're older than you were yesterday.

I have a little bit of the opposite of an issue: I look very young. Relatively speaking, I am still young of course. However, compared to what one expects of someone my age, I still look, well, like an undergraduate still trying to work out the most efficient paths from the dorm to campus.

It is the source of great amusement though. Sitting next to the emergency exit doors on airplanes I have been asked on multiple occasions "Sir, are you over 15? Because to sit there, you need to be over 15." I can coolly respond with a chuckle that I am, indeed, over 20, and people more often than not appear taken aback by that fact.

I still get carded at bars, as you would expect, and I imagine I will continue to be carded until I'm well into my 30's.Amusement aside, I do wonder whether my youthful appearance can be a double-edge sword. For all the visually appealing things that come with having a face that seems as though it belongs to a much younger person, certain professions seem to accord respect and achievement with how much wear and tear a face bears. Many people want to see a colleague whose appearance reflects "venerability," where battle scars take the form of wrinkles and crows-feet lining ones skin. One who doesn't look the part of serving in the trenches is doubted to have actually done the time in the trenches, and sadly can be treated more like an unwanted dilettante until further notice.

Maybe I should grow facial hair...

I'm currently working on developing models for a cognitive architecture called 'Polyscheme', and having quite an adventure with it.

I liken the architecture to riding a horse. There is a lot of machinery going on under there, that for the most part we don't understand. Just starting out with your partner in crime, it doesn't seem like it listens to you on even the most basic tasks. This is not the fault of the horse, but rather a consequent of your inexperience with mounting and riding the animal.

Horses don't like to be abused, and neither does Polyscheme. If you do mess with it, it messes with you back. It misbehaves. It doesn't do what you want or expect. It spits stuff back out at you in ways you don't understand.

Communicating with it at first can be tough. However, like many difficult tasks of this nature, the instinct of knowing what the horse wants or feels is one gained with constant work and training. You'll feel for the longest time that you're not making progress, and then *snap* all of a sudden you just get it. You can't put words to it, you can't explicate it to a bystander who hasn't shared a like experience, but you just get it.

They are both magnificent in their own way, capable of things we can't even imagine ourselves. But learning to communicate in a meaningful way so as to reach each other at a sub-linguistic level is a daunting task.

You can't learn to ride the animal any other way than getting on and trying not to die. You can't learn to model any other way than jumping in and dragging your mind through the mud.

Consider it like language-learning through immersion.

Just the other night I was hanging out with a few of my grad student friends at one of their place. It was already fairly late at night, maybe after 10PM or so, and I had already spent a fair amount of time in the lab that day (close to 9 hours). Needless to say, my mind was pretty exhausted.

Now, while hanging out with friends I usually don't have much of a problem keeping up with the conversation, so long as it doesn't stray into fields where I have little to no experience (engineering, business, cricket, etc...). The discussion's of the night were covering a wide range of topics, from research to professors to other details about our lives.

During the evening however, I noticed that I was having more and more trouble remaining fully entrenched in the conversation. My mind kept sinking into itself, and it felt not so much that I was fully engaged in the situation but more like a person inside a room observing the situation through a television screen. Of course I was physically there, but my mind was distracted.

It really was like watching a television show from within my own skull. Rather than being constantly bombarded with the sensory perceptions we all have that defines our existence in the world, I felt distanced. I felt as though the little man in my head could stand up and walk away from the television, that within my own mind I could leave the place where I physically was and...well, do something else.

I of course worked harder to maintain my place in the conversation, and it was a very interesting one too. The people were great, the food was great, the drink was great, and one should appreciate good company when it's offered because god knows, we miss these things when we don't have them.

My mind however seemed to be...distracted by something.

So that led me to ask myself: is all of the work I do making me dull? Am I so exhausted mentally at the end of the day that I can't engage engage people at the casual conversational level without being distracted by concerns of syntax, semantics, cognition, etc...?

Regardless, I hope that the friends I've made in the department can keep me grounded, and drag me back from when my mind sinks so deeply into my work that the little man inside my skull decides to just leave the television screen of my perceptions and represent his own little world using my own little representations and devices for thought.

All work no play may actually make one a dull boy. Let's not let that happen.

I happened across an article today, one that reports that researchers have developed a robot that can "deceive". The link: http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2010/09/robots-taught-how-to-deceive/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed:+wired/index+(Wired:+Index+3+(Top+Stories+2))&utm_content=Google+FeedfetcherA notable quote from Ronald Arkin in response to questions concerning how "ethical" it was to develop a robot with the capability of deception: “We have been concerned from the very beginning with the ethical implications related to the creation of robots capable of deception and we understand that there are beneficial and deleterious aspects. We strongly encourage discussion about the appropriateness of deceptive robots to determine what, if any, regulations or guidelines should constrain the development of these systems.”Before I begin discussing this briefly, I feel it necessary to point out that it is a little bit premature to be discussing how dangerous it to have robots that can deceive in existence. If you pay close attention to the wording of the researchers, they do tread carefully around just how successful their tests actually were. I do sense that the methods by which deceptive behavior was generated in the robots was not as complete a process by which humans use deception on a daily basis, and so was perhaps a more "hacked" behavior than being a result of complex cognitive processing. If it were the case that deception was the result of some sophisticated upper level reasoning, the ability to mislead another robot would certainly not be the only interesting behavior observed by the researchers, and the means by which the behavior was generated would form a substantial leap forward in current AI progress. That being said, it does not diminish the achievements of the group. Anyone who's done any research in AI will tell you just how difficult it is to generate even simple behaviors in artificial agents, be they completely encased in a computer or embodied as they are in the relevant experiment. So, at the very least, hat's off to that team for doing something pretty cool. Back on topic though. I've noticed a pattern in many AI researchers who take it upon themselves to at least consider the ethical ramifications of the work that they do every day. Even those who do not speak or seem to concern themselves with issues of the ethical concerns for results in AI have, I'm willing to bet, at some point considered the complications of incorporating what could potentially be an artificial agent into a perhaps less than prepared society. This pattern seems to be one of acknowledgement of the issues, but a fear/refusal to actually address them. Consider Dr. Arkin's quote above where he "encourages discussion about the appropriateness of deceptive robots..." He realizes at least on some level how complicated these issues are, but, like most researchers in the field, passes the buck to someone else. I feel as though nobody wants to handle the sticky issue of ethics, rights, and other such abstract notions that people have been wrestling with for ages. Nobody wants to handle this issue, even if it's their own creations that may someday render these concerns relevant to their society. It's a complicated issue with no good guys, and no bad guys. After all, at this point we have a lack of concrete examples to refer to to help guide our thoughts concerning ethics and AI. We've never handled man-made "golems" that caused us an existential crisis about what it means to be endowed with rights and entitled to fair treatment because of our personhood. So the fear and uneasiness with the issue is understandable. We're scientists after all, not politicians. At the same time, I don't believe that the questions of rights and personhood and other such quicksand concepts should be left to the politicians entirely. They have their own concerns. They have their own fanbase to appease, elections to win. Talking a good game and truly understanding the game by playing in it are two different things. We as AI researchers should begin to play a more active role in steering the treatment of what could someday come to be true AI agents. If it does happen, that we do create AI systems on the level of humans in all regards (which, if you read one of my previous posts, I actually feel is impossible for reasons I can't quite logically formulate), then we will be responsible for our creations, our children, and ensuring the best course of action for any child is best when the input of the parent is taken into account. It's a difficult issue, and I may actually be lighting the fire that burns me a bit by only pointing out the existence of clouds in the future while not really offering a starting point where which we'd build a shelter, but I feel it's time to start taking this issue to heart, even if it's hilariously premature to do so. The issues at the heart of this form an incredibly important subset of philosophy and society's concerns in general, so it's not unreasonable to simply apply them to the possibility of many of the abstract examples tossed around for ages becoming a concrete point in debate being grounded in the results of AI research. One of us should take that flag. Maybe it should be Chomsky. After all, this is his backyard.

I am an entire two weeks into my PhD here at RPI, learning to move and survive in academic circles I had only up until this point experienced only as an observer. From my father to the university life at Michigan, there was always an insulation from the truths of the life that awaits anyone who intends to graduate school in the future, and perhaps as a natural next step for those who survive this, a position as a Professor at an institution of higher learning.

This is a culture within a culture within a culture, the Cognitive Science Department at RPI within the culture of academia, within the greater culture that is the United States. It is complete with its own set of customs and traditions, a hierarchy of significance and respect that chains downwards from respected tenured senior faculty to us first year grad students still learning to strike out on our own. It has its own language, complete with a whole new set of connotations few people outside these circles would find pragmatic towards everyday living. "Funding" is no longer just a word for money, but a treasure chest that carries with it respect and the means by which one lives in this world. "Emeritus," well, come on. Most people outside academia don't even know what that means. "Tenure" is not just a protection for being fired or laid off, but here it's a sign of esteem, a goal held in such high regard that being considered for it in and of itself is a mark of respect.

And these words aren't even of the technical variety. Cognitive Science itself carries its own "buzz" words, words that anyone worth their salt in the field could, upon hearing the words utterance, fly off on some rambling tangent concerning the implications, connotations, and denotations of the term in ways seemingly irrelevant to anyone else in the room, save for those who already speak the language.

The culture is very unique, as is any culture. Of course, many of the standards rules of the containing culture do apply still. We still wash our hands when leaving the bathroom. We still close the door on the way out of the room. We still use a fork to pick up our food (although I'm starting to realize that depending on the food and the company, this is less and less strict than your parents would likely have you believe).

The key to any cultural learning is immersion. Hence, we neophytes attempt to absorb as much as we can (or at least we ought to). Observe the way people interact, they way they talk and communicate, the way the approach each other and the situations they frequently find themselves entwined in. You learn the customs through practice. You learn the language through communicating (although this is, admittedly, one of the more nerve-wracking experiences a young graduate student seems to face).

One hopes that with enough learning and time, we'll feel less like interlopers and more like natives.

Funny thing about this culture, of course, is that there are very few, if any, people who could claim to be natives. Nobody is born with a PhD, or even a PhD level understanding on any topic esoteric enough to be licensed as research field and thus capable of handing out Doctorates.

Thus, natives in the world of academia are illusions.

We are all interlopers in someone elses backyard.

For us in Cognitive Science, the backyard is probably Chomsky's.

I am currently having another bout with insomnia, my restless mind accelerating through a multitude of thoughts with little to no organization, rhyme, reason, or rhythm.

During this latest uncontrollable mental meandering, my thoughts turned to what it means to be in the field of cognitive science, and of course, A.I. A conversation I had a few months ago with someone caused me to reconsider many of the motivations and aspects of the weight of my work, in ways I'm only now coming to fully comprehend.

Once upon a time, I dreamt of being one of the minds who gave birth to true, strong artificial intelligence. I wanted to create an artificial mind that rivaled that of humans across all domains, to the point where the only thing that separated humans and artificial systems of intelligence would be the origin and biological makeup of the entity.

To me, the effects such a discovery would have on society had never truly struck a chord with me. Despite my philosophical background, I had always considered the work of a scientist to be principally concerned with scientific progress, and the treatment and incorporation into society the work of...well, someone else. After all, we as scientists have enough trouble as it is trying to understand the mechanisms of mind while simultaneously limited to using only our own mechanisms of mind.

Of course, societal impact of true AI had occurred to me. But such things as treatment of these entities, systems of rights, and other such ethical concerns were something I felt perhaps the human race would cope with over time and accrued experience, with ample leeway for growing pains.

In short, societal implications of my work was not my concern.

My thoughts gradually changed when presented with a different view, a new reason for caution.

As it was discussed, it was made explicit to me a realization that anyone who's been in the field of AI for a reasonable amount of time by a person who was not in the field itself: the human mind is a wonderful thing, of great complexity and majesty. There are things that occur within even the most basic of human thought processes that have proven to be extraordinarily resilient to even the most probing of minds and analysis. To try to reduce the majesty of human cognition to a sequence of 1's and 0's is perhaps missing the point of what makes the human mind special.

Think of the human mind as a beautiful one-way mirror. We can "peer" outwards from one side of this mirror, but looking into it from outside, we can only see a reflection of our own eyes staring at its surface, but never through it. The majesty of human cognition is preserved by this one-way mirror, the ultimate treasure we cannot see (yet). Majesty is preserved in mystery.

This was all well and good to me, although the weight of this fact didn't sink in until later. What was especially disturbing to me at the time was the following point made: in trying to create artificial intelligence, we run the risk of shattering the one-way mirror, and destroying what makes the human experience special, magical, majestic.

Our meddling intellect misshapes the beauteous form of things. We murder to dissect.

~William Wordsworth

Will we murder the beauty and mystery of the human mind in order to dissect it? And for what gain? So that we could have another feather to stick in our cap and scream out at the heavens "Look what man's intellect has discovered! Truly, are we not Gods?"

It took many months for me to contemplate this. It's to me a very weighty issue, one that strikes at the heart of my motivations for research. While I didn't want to give up my passion for my research (where our passions lie is largely not up to me anyways), the doubts leaking into my mind wanted of attention, for they spoke to me at a level of truth I could never explicate with words.

My passion for A.I. research and my fear of shattering the mirror both exist within my mind now, and have largely found ways of coexisting within those limited confines. While acceptance of the presence of both is certainly important to maintaining relevant aspects of my life, I have now been considering how they came to coexist together, my desires and my doubts in stark opposition to one another intuitively, yet standing together in my mind side by side. What is the relation to one another that allows me to keep going with my work?

There is at the heart of my research a very strong notion, a very strong opinion: yes, the human experience and the mind are amazing, beautiful, a wonderful harmony of chaos and order mixed in ways we cannot even begin to comprehend. Nor will we ever truly come to comprehend it.

The one-way mirror is unbreakable. We can strike, pound, hammer with all our might, but the very way the mind is constructed is impervious to our attempts at penetration. We are limited to the tools we are given, and these tools leave us poorly equipped to tear down the wall that separates our intellect from our minds.

Simply put, I am of the belief that it is impossible for us to truly understand what goes on in our minds to the level that would allow us to develop a complete theory of mind.

It is important for me to note here that this isn't to say we won't be able to create true A.I. someday. I am simply of the belief that if we are successful in doing so, it won't be as a result of us understanding the mind and its majesty. It will be done by circumventing this impossible problem, if at all.

So where does that leave me, a poor researcher in the field of cognitive science? It leaves me freedom, and the power to pursue my research to the end, without the fear of shattering the one-way mirror and throwing the mystery of the mind to the winds. For I can drive at my linguistics research, my philosophy research, my computer science research, all towards developing a model that would allow a system to understand natural language on some level, perhaps even a human's level, but no matter how deep I get, no matter how sophisticated my models become, they will only be able to stand outside that one-way mirror, and look in on what true majesty is like.

So do not worry (I tell myself constantly), the mystery of what makes human cognition spectacular is safe from our meddling intellects. The beauteous form of it preserved by its very nature, a security by obscurity.

In closing, the most powerful moment of the conversation was an act. It was an act that changed the way I thought, who I was, and who I was to become. It was an act that carries more significance and weight than any infinite sequence of 0's and 1's could ever express.

For just one instant in time, I looked into the one-way mirror, and saw someone standing beside me, smiling back through the reflection.

Almost two years ago when President Obama took office, he probably had no idea what it was exactly he was inheriting. While I personally didn't vote (I was somewhat confused as to where I stood politics-wise), if I had I would have cast my vote in his favor. He was (and is) young, energetic, an excellent speaker and natural leader, and a face that we could all rally around.

But what I did also notice was the ridiculous hoopla that his reputation had garnered. People (especially in Ann Arbor) had him pegged as the savior, the one who would change everything, a superman hiding among us only to now come forward to lead us to peace and happiness.

While a supporter of our current president, I expressed mild frustration at this spirit. Although our president is a very smart man, and very capable of leading our country, he is still human in all respects. He can't change everything instantaneously, he's going to make mistakes, he's going to anger and seemingly betray those who once held him in high-esteem.

So I thought the best way I could support Pres. Obama was to remind people of this fact, lest they be disappointed following election day, where they went to bed with God and woke up with a human instead. I just hoped that people who worshipped Pres. Obama would eventually realize that he's imperfect as the rest of us, and only capable of so much.

Once that is understood, we can really get to work, and let the President get to his work as well. I'm sure he's a very busy man, just like you and I. My bosses don't expect perfection out of me. Perhaps we shouldn't expect it out of him. After all, he is, at least in spirit, in our employ.

All courtesy of Matt Might. 1. A graphical representation of the PhD student's life: http://matt.might.net/articles/phd-school-in-pictures/This illustrates to me just how hard it is to make one's life's work meaningful to those not already acquainted in the field. What means the world to us is largely irrelevant to the vast majority of observers. Depressing? Perhaps, but it's also motivation to keep going, and also try to make your work as understandable as possible to as many people as possible. 2. Three important qualities for the successful graduate student: http://matt.might.net/articles/successful-phd-students/The fact that you don't have to be smart to do a PhD certainly works in my favor. I've never been the brightest or the best, never stood out incredibly among my peers for the brilliance of my analysis or study. Of note to me was an occasion where my philosophy professor outright said to my face "Richard, your grades are mediocre." Not the most positive message to take home. Fortunately though, what I do have is determination, and grit. I hope that can carry me through. That and I'm very familiar with failure. ...I'm starting to get the impression that becoming depressed about one's previous life is a good way to start graduate school.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed