It should be readily apparent to people that there is a very strong connection between language and cognition. The way we use words to communicate ideas offers us insight into cognitive states and processes that would not become that obvious were it not for either there repeated occurence in natural language as a "rule" or their occasional, seemingly unregulated occurence as an "exception." Not only is there key insight into the mind that can be found by studying the consistencies that have developed seemingly independently across all human languages (concepts of nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc...), it is important to note the effect words can have on the very cognitive processes long thought to produce natural language.

Our thoughts, feelings, and emotions can be influenced simply by the way an idea is being conveyed to us. For instance, consider the following utterances:

1. "the presentation was unsuccessful"

2. "the presentation was an utter catastrophe"

3. "the presentation was poor"

These all could refer to the exact same presentation, even possibly from the same perspective. In conversation, one could coherently utter all three of these sentences, and it would not be apparent to the listener that there was any form of inconsistency being observed.

However, the influence the word selection has on an observer who is not familiar with the actual presentation to which the sentences refer to is quite stark. (1) makes the presentation seem like it was generally not well accepted by the audience, although by no means on the scale of being terrible. (2) seems to make the presentation look god-awful, as if the presenter was chased off the stage with rotten tomatoes. (3) seems to walk a middle ground between the two. (3) may even be more special than that, referring to how well put together a presentation is as opposed to (1) and (2) that may just refer to how well it is received by the public (as anyone who's done presentation's knows, these are two very distinct concepts).

Point is, the way an object is referred to linguistically influences our mental conception of that object, even if we had direct viewing access to it. A famous study (which I will regrettably fail to cite) illustrates the effects a linguistic description of an accident has on the representation of the severity of the accident in witnesses, even if the witness should have had a first hand account of the accident's severity.

Extending this argument, we can look back at some of history's most influential people. To start with a very stark example, consider Adolf Hitler.

One of the primary architects of evil, he defined what it meant to be "evil" in the 20th century, and continues to do so today long after his death at the end of World War II. He was responsible for millions of deaths and untold suffering during a relatively short period of time.

For all of the evil he caused, he himself probably did not pull to many triggers during that period. Rather, he was able to persuade others to do it for him. He held his country in a state of rapture, his firebrand leadership capturing the heart and eventually brainwashing a nation into blind acceptance of what the rest of the world (and with time the German citizens themselves) would regard as insanity.

What gave him such power over a nation was his tongue. It did not matter how radical his ideas were, or what evil they contained and could potentially result in. It was what he said, his words and their effects, that brought a nation to its feet, and eventually, to arms. It was his words that turned a country against a group of people, and painted them as menaces and degenerates. It wasn't his fingers that pulled the trigger, it was the ideas planted in the minds of his followers with words that did it.

In effect, words were the weapon which he used to nearly destroy Europe, and possibly the world had he succeeded.

It is a weapon we are all armed with, to varying degrees of skill. It is deadly in the most powerful of ways: while it probably can't hurt your body, it can influence the mind in ways you don't even realize.

The pen really is mightier than the sword, and is only going to become more so with the advent of mass communication. In our country, we protect the use of language with law. It is a weapon we are entitled to, and fairly so.

This only means that we, as observers to so much information and ideas, must constantly be on guard concerning the things we read or listen to. Fortunately, we all can use words freely, and understand them relatively well. Unfortunately, understanding the use of words does not guarantee a successful defense against dangerous and harmful ideas.

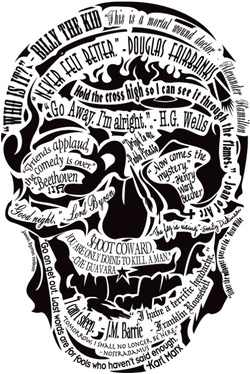

Language is a weapon. True understanding of the semantics of words can be a shield.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed