In all relevant senses of the word "change," the rise of the internet has changed the world. The nature of the world, and the way we view and respond to it. From the oldest stodgiest members of society to its youngest barely-mature-but-mature-enough-to-rap-on-a-keyboard constituents, the presence of vast amounts of information and data is an accepted part of the modern experience. It's changed, quite literally, the face and nature of society.

Including warfare, and the way societies wage it.

One can immediately point out that there doesn't seem to be a vast difference now between what we did a number of years ago in terms of waging war. We still have soldiers in the field. We still have men with guns and men in planes with bombs.

To this, one also has to remember that the availability of mass communications is still a relatively young, having only come to mass usage by the public in MY lifetime (which says something, because admittedly I am pretty young). Given the youth of the use of computer technology for a variety of different purposes, the prevalence of the technology in our daily lives truly is a phenomenal happening, and someday I can say with certainty historians will look back on this point in time and say "those were the days that everything we thought about the world shifted."

I predict that we are indeed witness the beginning of the way humans wage warfare, much the same way that the successful utilization of gunpowder revolutionized the art of killing in (relatively) ancient history. I predict that any form of military operation will presuppose the existence of technology "scouts" and "soldiers" pushing on a cyber frontier, invading borders of owned components of cyberspace. These cyber frontiers will be considered just as important as any countries physical borders, and perhaps even more so, as while a single intruder who proceeds a few miles past a border is not a cause for major, but a trained individual who can penetrate a cyber border is a potential storm of destruction and chaos. An individual, with the right know how, motivation, and resources, can potentially destroy not only the capabilities for an otherwise well equipped military to react and respond to threats, but also attack a nation's economy, infrastructure, capability for mass telecommunications, disrupt trade routes, or any number of sinister and/or subtle plans of varying levels of maliciousness.

I predict that countries with any reliance on technology will begin the setting up of these cyber borders and frontiers, jealously guarded by each nation's security personnel. The exact definition and what marks these boundaries will need to be established early on, and that will be the first sign of the major transition in warfare. When borders are established, it firmly establishes the distinction that is necessary for wars to be fought: this is what I own, that is what you own. If you touch what I own, it is an affront to me and my sense of autonomy. Do not touch what is mine.

When cyberspace is divided up among countries with power and influence in that same space, cyberspace ceases to simply be an avenue of communication, a plain where ideas are shared, and people are free to roam and interact...

It becomes a battlefield, where each civilian potentially holds a key to something of value to someone somewhere. Warfare will change. Conflict will change. Its soldiers will change as well.

What kind of soldiers will arise? I have my theories...and I have a feeling that at some point in the future, I will be helping to build an army. Problem is, I wonder if I ever did sign up for this kind of new war.

I'm not going to lie: the future scares me. The only thing more certain than my fear is the knowledge that I'm not alone in it.

Every day after a certain point in my life (a point that's proving exceptionally difficult to pinpoint), I began taking future quandary seriously. And what I saw...I didn't like.

It wasn't that I didn't have a future. I was always certain I did.

It wasn't that it was going to be difficult that I didn't like. I enjoy challenges, regardless of whether they're even relevant or necessary, or even worth pursuing in the least. A challenge is a challenge, and I'd climb a mountain just because it's there (except I wouldn't actually. I'm terrible with climbing).

No, what I didn't like was its murkiness. I always thought about it this way: to me, no way of dying is more terrifying than death by shark attack. I could be mauled by a tiger, fall out of a plane or cliff, or get hit by a truck, but just the thought of being consumed by a shark...well, it gets me in a way I'm not often got.

Why? Because up until they set their jaws in your skin, you don't see them clearly. You only see a silhouette distorted by the waves, unless you're looking at them through goggles. But regardless, it's that uncertainty of form that carried with it terror, dread, and a death less than ideal.

And so it is with the future. It's murky, and always will be. It was back then when I first began wondering about it, and it is now, even at the start of my graduate studies (although not so much the start anymore).

Will it ever be different? Will I ever have the certainty and comfort in knowing the future? Conceivably not.

I always hated leaving things in the hands of fate. But, ultimately, such things may just be out of our hands, no matter how much we struggle to control our world. Although I'm still on the fence on whether I'd prefer fate or absolute chaos (I have my theories that you either have one or the other, but that's a discussion for another day), maybe my notion of control is just an illusion...

Fine, I can live with that. But dammit if I'm going to surrender my autonomy without first dying for it.

Now, I am a cognitive scientist, which places me in a larger set of people: that consisting of scientists. Science is itself a mushy label with an equally mushy set of meanings. We have enough pseudo-sciences in existence to rival the whole accomplishments of what we would consider "real" science, as well as an equal number of people who would gladly hold their pseudo-science up against the most complicated tenets of string theory and quantum physics. Point is, what makes a field science is rather poorly defined, and I honestly don't see any rigorous or formulaic means of simplifying and defining the distinction itself.

What we can all agree on, at least to some extent, is that science is concerned with questions. These questions are big and small, perplexing or perhaps simple, of interest to us or not. Questions of matter, of existence and metaphysics, the nature of life, thought, our bodies and our minds. Questions of how we came to be, how things came to be the way they are, and how things could conceivably change or become. Science is composed of questions of all kinds.

Humanity, and even more so its scientists, find themselves in the middle ground of the universe and its questions. On a grand scale, we are caught between the beginning of time and the end of time. We are always wandering between ignorance and complete enlightenment, looking back at what we've learned through eons of experience and study as well as staring forward into all of the things we have yet to understand to even the slightest iota of truth. On a more individual scale, we display the same patterns of middle ground-ing. We neither always love, nor always hate. We are intelligent in some places, idiotic in others. We think we're better than some people, others we wish we could be instead. We're brave...sometimes. We're also cowards too of course. We're a middling and meddling species no doubt.

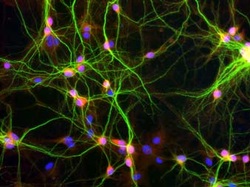

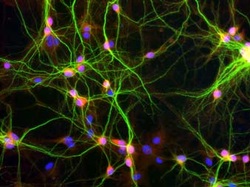

So it was a sort of "philosophical justice" when I realized that, in my mind, we are once again caught in the middle ground of two of the major questions facing science and humanity in the 21st century: the workings of the mind and the depths of the universe. The study of the human mind can be considered very roughly along two levels of analysis: high-level function and behavior, and biological/physiological changes that occur on the neuronal level. Regardless of which level of analysis you choose to focus on, the closeness of the object of understanding is as close to us as anything is. It forms the central core of any human and animal, and any conception of existence would be (quite literally) impossible without it. We can poke it, dissect it, (try to) replicate it in computers, hold it in our hands and take notes about its squishiness, and observe the end results of its functionality in ourselves and others. The mind is as close to us as anything could ever be.

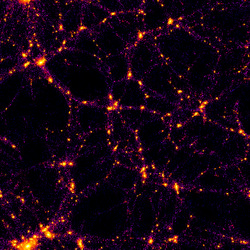

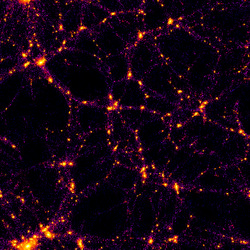

Stretching beyond our ability to touch, feel, or grasp is the sheer immensity of the universe. We have barely scratched the edges of our own atmosphere and remark to ourselves about how great an accomplishment that is (and don't get me wrong, it is a great accomplishment), and yet we all realize that we have only descended one inch into the depths of a great ocean of stars. Out there is something we can't grasp, something we can't hold or manipulate with our fingers. We can't poke it, we can't dissect it. We are instead largely confined to staring at it and marvelling at its splendor and awesomeness. It is as far from our grasp as anything could ever be.

Through this stark constrast, they share an important attribute: they embody two of the great mysteries that challenge the human race. As I mentioned before, science is about questions, and they don't get much bigger than this. To put it succinctly, the big questions for us are "what is the nature of that which is outside of us and beyond our grasp?" and "what is the nature of that which occurs inside of us, within the confines of our own bodily limits?"

So we are in the middle of two great mysteries, searching in both directions for answers to that which is closest to us and that which is farthest from us. In a telling moment from the Tron movie series, we are treated to two opposing rallying cries:

"In there...is our destiny."

"Out there...is our destiny."

For humans and scientists, whatever our destiny may be, it does not appear to have drawn any such distinctions between what is in there and what is out there. It is simply destiny.

The days I spend rather locked up in one room or another. Either in the laboratory, staring at the same computer screens and walls and whiteboards for what feels like days. Sometimes in the library, sitting at the tables and desks that all look alike, and can only be deemed unique by position in space rather than defining qualities or features. Were they children, they'd be identical twins devoid of uniqueness or character traits of interest.

So I spend days in earnest study, trudging slowly to no guarantees of success or meaning, all because there is hopefully a light at the end. While it feels depressing, there are moments of invigoration, when you feel a little flicker burn again for what you're working towards. Inevitably, it is suppressed by the sheer weight of what you expect of yourself of course, but ironically self-expectations are often times one of the things closest to us we have little to no control over.

A short story about Buddy:

On the last day I rode with him, 12/7, I went out to the outdoor ring to bring him in for tacking. It was dark, and I couldn't see that well. When I entered the ring and shut the gate behind me, a couple of the other horses in the ring were standing right in front of me, as soon as I turned around, staring at me, probably trying to get out, or at least get my attention.

All of a sudden, they were spooked by something and scattered. And then there was Buddy walking up to me. He stopped a foot in front of me, head bowed and eyes and ears alert. He had snuck up on the other horses in front of me from behind, and lay claim to his rider.

The proudest moment of my short career as a rider came when I wasn't even in the saddle.

Buddy passed away this December.

So here's to you Buddy. You really were too good to me. Rest in peace.

So Wikileaks is sort of a mess, isn't it?

People are up in arms.

"Anonymous" is on the march.

The internet's usual wild west nature just took on a whole new feel.

At the risk of falling prey to the internet wolves, I'm going to go out on a limb and say that...I don't really like anyone in this mess.

I dislike Wikileaks.

I dislike Julian Assange.

I STRONGLY dislike censorship.

I just as STRONGLY dislike Anonymous.

I don't have a side. I just think you're all stupid.

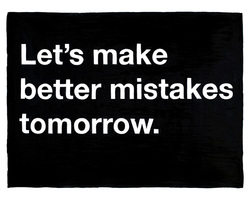

I hope they are better mistakes. Today's mistakes suck. I sit here on the 4th floor of the Folsom Library at RPI, overlooking the quad, with its trees and people waving and walking their respective ways. It's been about 3 months since I first stepped off the plane in Troy, NY, and I still remember that day pretty clearly.

Obviously, the steps I took off the tarmac that day were ones I should have been prepared for, given that I had an entire summer to prepare myself for it. Preparation is one thing. Implementation is something entirely different. It's what separates watching "Jackass" from actually landing in the hospital.

So it has come to pass that in the blink of an eye, I've been here for a while now. I once thought that the time it took to complete a Doctorate felt like an interminable amount of time. I've since come to re-evaluate that stance, having dipped my feet in the academic pool for long enough. The life of an academic is a rapid one in this stage, and with its flow leaves a lot of uncertainty in the air. In a profession that treasures good questions, it's often the questions outside of our research that can be the most damning.

When will I finish my PhD?

When will they figure out that I am in fact an idiot and tricked them into accepting me?

Where will I do a Post-Doc?

Who in their right mind would accept me as a Post-Doc in the first place?!

...am I missing the most valuable part of young life by spending it holed up in a lab?

There are a lot of mushy ways to define meaning. As a lexical semanticist, I can think in starkly academic terms the meaning of...meaning. But as a human being, there is a lot more weight to the word than can be lexicalized. At least formally.

So let's consider for a moment what I mean when I say "meaning." When I apply the term to the overall human experience, it pertains to something that gives a moment, a period, or a lifetime something of importance. Thus, meaning to me is considered at least in part to be temporally relevant. It is as temporally relevant as the fact that when we walk, there must be one step that occurs after each step, and ongoing until we decide to stop. It doesn't matter how far we can break down our experience over a lifetime, the meaningful things are always there.

Finding meaning is perhaps even more difficult than defining it. Perhaps it's one of those "I don't know what it is, but I know it when I see it" kinda deals. The good thing about this approach is that it relativizes what is meaningful to a person to the person itself. Thus, there are many approaches to life, and meaning comes to everyone in unique ways, as it is uniquely defined by that individual.

Regardless, I still feel as though meaningless acts and lives are not uncommon. Perhaps it is difficult, even impossible, to judge fairly the way people search for meaning in their lives. Regardless, if one didn't have some notion of what they felt was a waste of life then they wouldn't be able to guide any of their important decisions, much less themselves live a meaningful life under their own definitions.

So I judge...it's impossible not to. And it does sadden me a bit to see people sometimes surrender the desire for a meaningful life, and waste time with meaningless actions.

But these judgments are all through the eyes of ones own definitions, and are implicitly unfair as a result. What's important is realizing this, and understanding there are many different ways people find meaning.

I'm certain someone out there after all finds the way I've chosen to live my life is meaningless and wasteful (anyone who's ever criticized me for selecting Philosophy as a course of study would agree). Ultimately, you can only shake your head, and hope they themselves realize to see things through your eyes.

It'll never happen of course, but it's a nice thought.

"Loomis and Beall argued that an internal model of plant dynamics would be supported by successful control of a vehicle after vision is removed, but current evidence shows that driving performance degrades sharply under these conditions."

~From The Dynamics of Perception and Action by

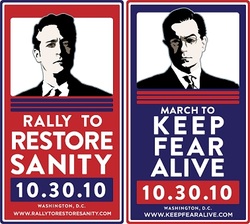

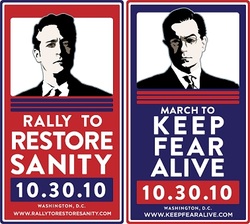

I was originally intending this weekend to attend the rally being staged in D.C. this weekend, hosted by Comedy Central personalities Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert.

Unfortunately, I was unable to head down to D.C. due to a list of items I need to do here (graduate school isn't all fun and games). So, instead, I am working out of one eye, and watching the live web stream of the rally out of my other. Multi-tasking? Like a boss.

That being said, the intention of the rally is, as you could infer from the titles (and taking into account the tongue-in-cheek character of Stephen Colbert), is to call us back to reason. It seems we exist in tempestuous times with an ever more polarizing political climate. Midterm elections are coming up, and for Democrats it appears as though the shift in power to their side may be rapidly coming to a close, if not now in the near future.

The many people who first helped place many Democratic leaders into power in the first place are disillusioned, the magic that permeated the 2008 campaign wearing off to reveal a pumpkin.

I hate to say I told you so, so I won't. But for us who do prefer sanity, as the rally mentioned above hopes to bring back to the forefront, it was easy to predict this. Let's start at the top: President Barack Obama.

Many of us who supported Mr. Obama during the 2008 presidential campaign made him to be some kind of god. We portrayed him as Superman, one capable of things never before accomplished. We thought him a legend before he had actually accomplished anything at the presidential level, and we annointed him based on potential rather than accomplishment.

It was, to me, insane.

I supported him, and I thought him the best candidate for the job. But the people on his side were simply, for lack of a better word, insane. I just wanted to take so many people by the lapels and shake them, and tell them "No! He's only a man!" Albeit a good one, and well qualified for the position of president.

Unfortunately, it's insanity that helped put him there, rather than real, honest assessment of who he is and what he can do. Please, put away the capes people. You elected a man, not a god.

In these times, we could all use a little bit more sanity, and that applies to all people in all parties. For those people who still think Obama's a god (and I suspect there are fewer of you now than 2008): be reasonable! For those who flip flop from one extreme to the other: be reasonable!

People aren't gods. Neither are they demons. I assure you, Obama can't save the world with his power. At the same time, I assure you, John McCain would not have destroyed the world had he been elected. George W. Bush was not the spawn of satan. Dick Cheney is not an American mini-Hitler. Rush Limbaugh in my opinion is still a douche, but he's entitled to his opinions.

Regardless, let's be reasonable for once. And have reasonable expections as well.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed