Words are a fascinating little thing, the constituents of communication. We use them for everything, from ordering a hamburger to ordering our two-year old off the coffee table. They can be poetic, or they can rough. They can be fluid, or they can be broken. They can make sense in particular arrangements, be totally impossible to understand in others, and covering every space in between those two ends.

I'm thinking these days about emotionally loaded words. Consider some classics:

adore

kiss

hold

touch

l#ve (censored for the faint of heart. it is a four letter word after all)

This five words are a tiny fraction of words that could have significant emotional meaning. Of course, emotional meaning is contingent upon pragmatic factors. For instance, to say "I adore donuts" has less emotional weight than expressing the same verb to take as its object a person of particular value to you (save for donut junkies. You know who you are). However, when placed in the emotional environment as I just did, many of us can already picture moments from their past where these words went beyond simply a lexical definition that fit into a grammatical framework.

These little pieces, little building blocks, when in the right place both grammatically and pragmatically, have invisible strings that tie themselves to parts of us we have little conscious access to. We do not even need to put them in particular concrete contexts to feel something about these words, something intuitively special about their usage and their weight.

We can say things are only words, but we all should know better. Yes, in some sense they are only words. My very first car was, well, only a car (and honestly, not a very good one at that). However, just its place in my memory makes that car more than just a car to me. It's something personal to me, more important than just another car I may see driving down the street.

I'm sure we all can relate in some way, and so it is with words. We all have very different experiences tied to words of emotional relevance, yet I hypothesize that they all generate similar feelings within each of us. On some level, we can all relate with each other about words of emotional weight.

So yes, they are only words. But words aren't just a means of communicating ideas. They are also a means of communicating emotions, desires, beliefs, and the things we hold dear and essential to the characteristics that make us who we are. Don't underestimate their weight.

The new design was screwing with the layout unfortunately. I hope to get some time this weekend to rebuild and make this site a little more...attractive. Keep in touch.

My website will be undergoing a redesign this weekend. Stay tuned!

I'm currently working on developing models for a cognitive architecture called 'Polyscheme', and having quite an adventure with it.

I liken the architecture to riding a horse. There is a lot of machinery going on under there, that for the most part we don't understand. Just starting out with your partner in crime, it doesn't seem like it listens to you on even the most basic tasks. This is not the fault of the horse, but rather a consequent of your inexperience with mounting and riding the animal.

Horses don't like to be abused, and neither does Polyscheme. If you do mess with it, it messes with you back. It misbehaves. It doesn't do what you want or expect. It spits stuff back out at you in ways you don't understand.

Communicating with it at first can be tough. However, like many difficult tasks of this nature, the instinct of knowing what the horse wants or feels is one gained with constant work and training. You'll feel for the longest time that you're not making progress, and then *snap* all of a sudden you just get it. You can't put words to it, you can't explicate it to a bystander who hasn't shared a like experience, but you just get it.

They are both magnificent in their own way, capable of things we can't even imagine ourselves. But learning to communicate in a meaningful way so as to reach each other at a sub-linguistic level is a daunting task.

You can't learn to ride the animal any other way than getting on and trying not to die. You can't learn to model any other way than jumping in and dragging your mind through the mud.

Consider it like language-learning through immersion.

Just the other night I was hanging out with a few of my grad student friends at one of their place. It was already fairly late at night, maybe after 10PM or so, and I had already spent a fair amount of time in the lab that day (close to 9 hours). Needless to say, my mind was pretty exhausted.

Now, while hanging out with friends I usually don't have much of a problem keeping up with the conversation, so long as it doesn't stray into fields where I have little to no experience (engineering, business, cricket, etc...). The discussion's of the night were covering a wide range of topics, from research to professors to other details about our lives.

During the evening however, I noticed that I was having more and more trouble remaining fully entrenched in the conversation. My mind kept sinking into itself, and it felt not so much that I was fully engaged in the situation but more like a person inside a room observing the situation through a television screen. Of course I was physically there, but my mind was distracted.

It really was like watching a television show from within my own skull. Rather than being constantly bombarded with the sensory perceptions we all have that defines our existence in the world, I felt distanced. I felt as though the little man in my head could stand up and walk away from the television, that within my own mind I could leave the place where I physically was and...well, do something else.

I of course worked harder to maintain my place in the conversation, and it was a very interesting one too. The people were great, the food was great, the drink was great, and one should appreciate good company when it's offered because god knows, we miss these things when we don't have them.

My mind however seemed to be...distracted by something.

So that led me to ask myself: is all of the work I do making me dull? Am I so exhausted mentally at the end of the day that I can't engage engage people at the casual conversational level without being distracted by concerns of syntax, semantics, cognition, etc...?

Regardless, I hope that the friends I've made in the department can keep me grounded, and drag me back from when my mind sinks so deeply into my work that the little man inside my skull decides to just leave the television screen of my perceptions and represent his own little world using my own little representations and devices for thought.

All work no play may actually make one a dull boy. Let's not let that happen.

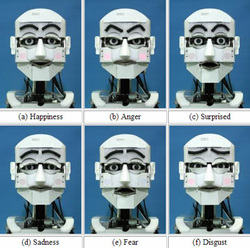

I happened across an article today, one that reports that researchers have developed a robot that can "deceive". The link: http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2010/09/robots-taught-how-to-deceive/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed:+wired/index+(Wired:+Index+3+(Top+Stories+2))&utm_content=Google+FeedfetcherA notable quote from Ronald Arkin in response to questions concerning how "ethical" it was to develop a robot with the capability of deception: “We have been concerned from the very beginning with the ethical implications related to the creation of robots capable of deception and we understand that there are beneficial and deleterious aspects. We strongly encourage discussion about the appropriateness of deceptive robots to determine what, if any, regulations or guidelines should constrain the development of these systems.”Before I begin discussing this briefly, I feel it necessary to point out that it is a little bit premature to be discussing how dangerous it to have robots that can deceive in existence. If you pay close attention to the wording of the researchers, they do tread carefully around just how successful their tests actually were. I do sense that the methods by which deceptive behavior was generated in the robots was not as complete a process by which humans use deception on a daily basis, and so was perhaps a more "hacked" behavior than being a result of complex cognitive processing. If it were the case that deception was the result of some sophisticated upper level reasoning, the ability to mislead another robot would certainly not be the only interesting behavior observed by the researchers, and the means by which the behavior was generated would form a substantial leap forward in current AI progress. That being said, it does not diminish the achievements of the group. Anyone who's done any research in AI will tell you just how difficult it is to generate even simple behaviors in artificial agents, be they completely encased in a computer or embodied as they are in the relevant experiment. So, at the very least, hat's off to that team for doing something pretty cool. Back on topic though. I've noticed a pattern in many AI researchers who take it upon themselves to at least consider the ethical ramifications of the work that they do every day. Even those who do not speak or seem to concern themselves with issues of the ethical concerns for results in AI have, I'm willing to bet, at some point considered the complications of incorporating what could potentially be an artificial agent into a perhaps less than prepared society. This pattern seems to be one of acknowledgement of the issues, but a fear/refusal to actually address them. Consider Dr. Arkin's quote above where he "encourages discussion about the appropriateness of deceptive robots..." He realizes at least on some level how complicated these issues are, but, like most researchers in the field, passes the buck to someone else. I feel as though nobody wants to handle the sticky issue of ethics, rights, and other such abstract notions that people have been wrestling with for ages. Nobody wants to handle this issue, even if it's their own creations that may someday render these concerns relevant to their society. It's a complicated issue with no good guys, and no bad guys. After all, at this point we have a lack of concrete examples to refer to to help guide our thoughts concerning ethics and AI. We've never handled man-made "golems" that caused us an existential crisis about what it means to be endowed with rights and entitled to fair treatment because of our personhood. So the fear and uneasiness with the issue is understandable. We're scientists after all, not politicians. At the same time, I don't believe that the questions of rights and personhood and other such quicksand concepts should be left to the politicians entirely. They have their own concerns. They have their own fanbase to appease, elections to win. Talking a good game and truly understanding the game by playing in it are two different things. We as AI researchers should begin to play a more active role in steering the treatment of what could someday come to be true AI agents. If it does happen, that we do create AI systems on the level of humans in all regards (which, if you read one of my previous posts, I actually feel is impossible for reasons I can't quite logically formulate), then we will be responsible for our creations, our children, and ensuring the best course of action for any child is best when the input of the parent is taken into account. It's a difficult issue, and I may actually be lighting the fire that burns me a bit by only pointing out the existence of clouds in the future while not really offering a starting point where which we'd build a shelter, but I feel it's time to start taking this issue to heart, even if it's hilariously premature to do so. The issues at the heart of this form an incredibly important subset of philosophy and society's concerns in general, so it's not unreasonable to simply apply them to the possibility of many of the abstract examples tossed around for ages becoming a concrete point in debate being grounded in the results of AI research. One of us should take that flag. Maybe it should be Chomsky. After all, this is his backyard.

I am an entire two weeks into my PhD here at RPI, learning to move and survive in academic circles I had only up until this point experienced only as an observer. From my father to the university life at Michigan, there was always an insulation from the truths of the life that awaits anyone who intends to graduate school in the future, and perhaps as a natural next step for those who survive this, a position as a Professor at an institution of higher learning.

This is a culture within a culture within a culture, the Cognitive Science Department at RPI within the culture of academia, within the greater culture that is the United States. It is complete with its own set of customs and traditions, a hierarchy of significance and respect that chains downwards from respected tenured senior faculty to us first year grad students still learning to strike out on our own. It has its own language, complete with a whole new set of connotations few people outside these circles would find pragmatic towards everyday living. "Funding" is no longer just a word for money, but a treasure chest that carries with it respect and the means by which one lives in this world. "Emeritus," well, come on. Most people outside academia don't even know what that means. "Tenure" is not just a protection for being fired or laid off, but here it's a sign of esteem, a goal held in such high regard that being considered for it in and of itself is a mark of respect.

And these words aren't even of the technical variety. Cognitive Science itself carries its own "buzz" words, words that anyone worth their salt in the field could, upon hearing the words utterance, fly off on some rambling tangent concerning the implications, connotations, and denotations of the term in ways seemingly irrelevant to anyone else in the room, save for those who already speak the language.

The culture is very unique, as is any culture. Of course, many of the standards rules of the containing culture do apply still. We still wash our hands when leaving the bathroom. We still close the door on the way out of the room. We still use a fork to pick up our food (although I'm starting to realize that depending on the food and the company, this is less and less strict than your parents would likely have you believe).

The key to any cultural learning is immersion. Hence, we neophytes attempt to absorb as much as we can (or at least we ought to). Observe the way people interact, they way they talk and communicate, the way the approach each other and the situations they frequently find themselves entwined in. You learn the customs through practice. You learn the language through communicating (although this is, admittedly, one of the more nerve-wracking experiences a young graduate student seems to face).

One hopes that with enough learning and time, we'll feel less like interlopers and more like natives.

Funny thing about this culture, of course, is that there are very few, if any, people who could claim to be natives. Nobody is born with a PhD, or even a PhD level understanding on any topic esoteric enough to be licensed as research field and thus capable of handing out Doctorates.

Thus, natives in the world of academia are illusions.

We are all interlopers in someone elses backyard.

For us in Cognitive Science, the backyard is probably Chomsky's.

Don't you ever wish sometimes that memories were packable, that we could take certain elements of our past and put them away in little black boxes for storage? We could store these little black boxes in the back of our mind, camouflaged against the backdrop of the darkness of the deepest recesses. Hidden in the nooks and crannies of our own cognition, they could be held there, safe and protected from any interference.

And protected there they would lie, until we were ready to reopen them. Then, upon opening up these little black boxes, we would reveal the old memories long removed through the passage of time, held in ways so they couldn't hurt us.

The black boxes are there just as much to protect us from them as them from damage.

Opening up the box, and letting out the ghosts, the memories would be returned to a luster and shine that felt new, felt novel, was exciting again. They would be just as we left them so long ago, still permeating with the smell of what once was, and what you pray every night might be once again.

At the same time, these memories wouldn't be new, of course. They'd be old in a very important way, attached to a past you. But therein lies the joy of opening an old box: it will be both familiar and new, strange to who you are now in a way, but influential on who you were once. We as humans are never truly removed from our pasts, so maybe, just maybe, there is hope in little black boxes for a future.

A future where the memories don't need to be hidden in those little black boxes.

When I was growing up in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, there were few things I spent more time doing than playing hockey. Like so many of the kids in my town, I entertained dreams of someday playing in the NHL, making a name for myself on the biggest stages and brightest lights the world of ice hockey had to offer.

Ultimately, it was not to be. I pushed and struggled against the bounds of my own physical shortcomings, but work ethic can only get you so far in sports.

That, and I was screwed over by my own birth date.

You see, the way age groups in youth hockey are defined is strictly by the year of birth. People born in 1986 were one group, people in '87 another, and so on and so forth. Under this system, someone born in January of one year is placed in the same group as someone born in December, nearly a full year's difference in age, and of course, physical development.

I fell into the latter category, which only compounded the fact that I wasn't very big or athletic to begin with. That being said, I always had this notion that even with all of the challenges I faced, I could become something with simple work and drive.

Call it the 'romantic movie syndrome for athletes.' Think about it: I tend to criticize people who believe too much in the romantic fairy tales of perfection perpetuated in the media. We are a group of individuals raised on Disney, with this idea that Prince Charming is going to sweep in and take the damsel from trouble to a beautiful castle and happiness ever after. So we think "wow, am I not worth that trouble as well?" and we wait and wait...and wait. Eventually we realize that there is no Prince Charming, and what's worse, we've spent so much time waiting for perfection that we've missed out on the real valuable people in life: the ones who's messes and scars we see and know well, but somehow manage to stick around with us.

But I digress. The point is, I may criticize this sort of behavior, but young athletes are raised on this too. Rudy, Hoosiers, The Mighty Ducks. All uplifting, and your team always wins against incredible odds. Young athletes watch these movies, and are instilled with passion and fire to accomplish a goal so few ever will even taste, so much as fulfill.

Not to say that one shouldn't dream of course. It's a tenuous balance I feel, to dream and to understand one's own penchant for failure.

Regardless, I've signed up to play hockey again here, in order to reconnect with the sport that plays a large role in who I am today. While I haven't skated in years, the discipline, the desire, the drive all have stayed with me from the days I tempered with early morning practices and late night conditioning sessions. While ultimately, the work didn't bring my abilities to a high enough levels to even make it to College hockey, I learned a lot along the way.

Hopefully, hockey now can serve a new purpose for me: help me maintain my sanity.

In no particular order... Pamplona, Spain Frankfurt, Germany London, England Orleans, France Prague, Czech Republic Lhasa Valley, Tibet Somewhere in Chile Manipal, India Dubai, UAE Stockholm, Sweden (for the blondes) Thailand (for the martial arts) Japan (also for the martial arts)

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed