Now, I am a cognitive scientist, which places me in a larger set of people: that consisting of scientists. Science is itself a mushy label with an equally mushy set of meanings. We have enough pseudo-sciences in existence to rival the whole accomplishments of what we would consider "real" science, as well as an equal number of people who would gladly hold their pseudo-science up against the most complicated tenets of string theory and quantum physics. Point is, what makes a field science is rather poorly defined, and I honestly don't see any rigorous or formulaic means of simplifying and defining the distinction itself.

What we can all agree on, at least to some extent, is that science is concerned with questions. These questions are big and small, perplexing or perhaps simple, of interest to us or not. Questions of matter, of existence and metaphysics, the nature of life, thought, our bodies and our minds. Questions of how we came to be, how things came to be the way they are, and how things could conceivably change or become. Science is composed of questions of all kinds.

Humanity, and even more so its scientists, find themselves in the middle ground of the universe and its questions. On a grand scale, we are caught between the beginning of time and the end of time. We are always wandering between ignorance and complete enlightenment, looking back at what we've learned through eons of experience and study as well as staring forward into all of the things we have yet to understand to even the slightest iota of truth. On a more individual scale, we display the same patterns of middle ground-ing. We neither always love, nor always hate. We are intelligent in some places, idiotic in others. We think we're better than some people, others we wish we could be instead. We're brave...sometimes. We're also cowards too of course. We're a middling and meddling species no doubt.

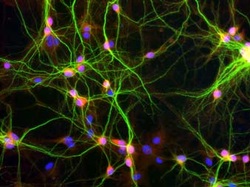

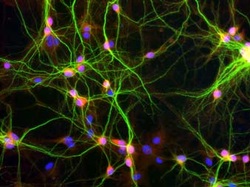

So it was a sort of "philosophical justice" when I realized that, in my mind, we are once again caught in the middle ground of two of the major questions facing science and humanity in the 21st century: the workings of the mind and the depths of the universe. The study of the human mind can be considered very roughly along two levels of analysis: high-level function and behavior, and biological/physiological changes that occur on the neuronal level. Regardless of which level of analysis you choose to focus on, the closeness of the object of understanding is as close to us as anything is. It forms the central core of any human and animal, and any conception of existence would be (quite literally) impossible without it. We can poke it, dissect it, (try to) replicate it in computers, hold it in our hands and take notes about its squishiness, and observe the end results of its functionality in ourselves and others. The mind is as close to us as anything could ever be.

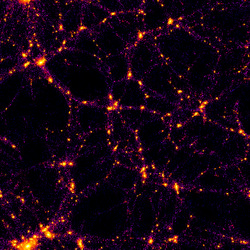

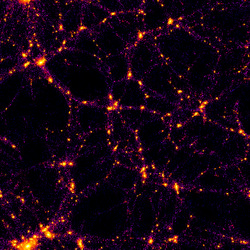

Stretching beyond our ability to touch, feel, or grasp is the sheer immensity of the universe. We have barely scratched the edges of our own atmosphere and remark to ourselves about how great an accomplishment that is (and don't get me wrong, it is a great accomplishment), and yet we all realize that we have only descended one inch into the depths of a great ocean of stars. Out there is something we can't grasp, something we can't hold or manipulate with our fingers. We can't poke it, we can't dissect it. We are instead largely confined to staring at it and marvelling at its splendor and awesomeness. It is as far from our grasp as anything could ever be.

Through this stark constrast, they share an important attribute: they embody two of the great mysteries that challenge the human race. As I mentioned before, science is about questions, and they don't get much bigger than this. To put it succinctly, the big questions for us are "what is the nature of that which is outside of us and beyond our grasp?" and "what is the nature of that which occurs inside of us, within the confines of our own bodily limits?"

So we are in the middle of two great mysteries, searching in both directions for answers to that which is closest to us and that which is farthest from us. In a telling moment from the Tron movie series, we are treated to two opposing rallying cries:

"In there...is our destiny."

"Out there...is our destiny."

For humans and scientists, whatever our destiny may be, it does not appear to have drawn any such distinctions between what is in there and what is out there. It is simply destiny.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed